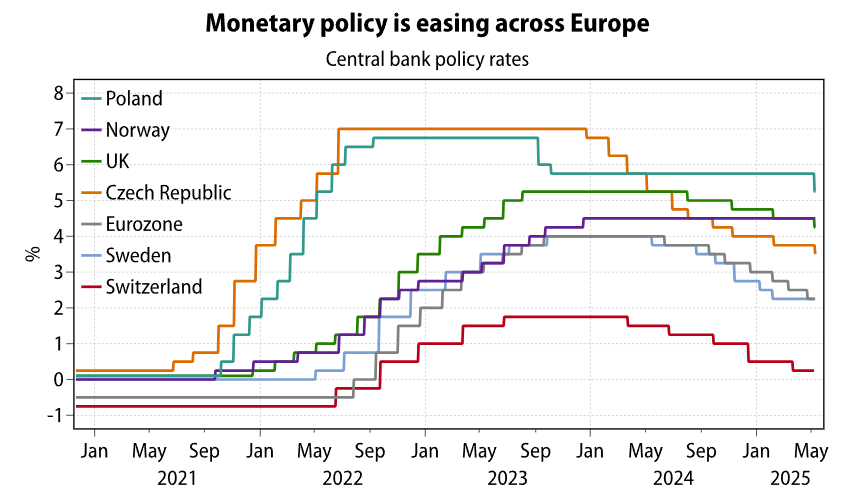

Europe’s rate-setters are moving in convoy again, trimming policy levers almost in lockstep even as Washington stands pat. Their logic is brutally simple: a tariff-induced chill on global demand is undercutting prices faster than any home-grown wage heat can offset, so the inflation target wins and the policy rate falls. That common diagnosis is welding together a region-wide easing cycle just as the Federal Reserve finds itself immobilised by a two-front war on jobs and prices.

The US Federal Reserve sat on its hands Wednesday. Not so central banks in Europe, which displayed no such caution. The same day, the Czech National Bank and the National Bank of Poland cut their policy interest rates, followed on Thursday by the Bank of England. Plus the central banks of Sweden and Norway issued guidance that they are poised to cut in the coming months.

This divergence reflects the differing policy calculus on either side of the Atlantic. In the US, the shock of the tariff war threatens to push up both inflation and unemployment, creating tension between the Fed’s two mandates. In addition, Fed policymakers are anxious not to be seen to be bowing to pressure from the White House to cut rates. All this militates against policy loosening.

In contrast, the decision for European central banks with their single focus on inflation is much simpler. In theory, Europe’s central bankers must weigh the deflationary impact of the negative external demand shock created by US tariffs against the domestic inflationary effects of retaliatory tariffs imposed by Europe.

But in practice, the temperate response of European policymakers to Donald Trump’s tariffs so far has kept any domestic inflationary effects in check. This leaves European central banks facing an unambiguously deflationary shock—compounded by cheaper energy prices and the depreciation of the US dollar.

This has made easing easy. After the European Central Bank cut its policy rate by -25bp to 2.25% on April 17, this week the Czech National Bank followed with a -25bp cut to 3.5%, and the National Bank of Poland with a -50bp cut to 5.25%, resuming a rate cut cycle which had been on pause since October 2023. Similarly, the Bank of England cut by -25bp, reducing its policy rate to 4.25%.

In Northern Europe, the Riksbank and Norges Bank kept their policy rates unchanged on Thursday. But having previously offered guidance that January’s cut to 2.25% marked the end of its rate cut cycle, the Riksbank opened the door for renewed rate cuts. Meanwhile Norges Bank, the only central bank in Europe not to have cut rates in this cycle, said it will most likely reduce its policy rate over the course of 2025.

Elsewhere, the Swiss National Bank is even likely to reintroduce zero interest rates when it meets on June 19.

Europe’s monetary policy calculus isn’t wholly straightforward. Beyond the trade shock, central banks still have lingering concerns about domestic inflation, visible in fast-rising service prices and accelerated wage growth.

As a result, the Bank of England, which faces the highest services inflation (and the smallest growth shock from US tariffs) pushed back against market expectations of faster rate cuts on Thursday.

But the bottom line is that central banks across Europe are all easing monetary policy at the same time, with Trump’s tariff shock eliminating any risk that they will halt their easing cycles prematurely.

So far, foreign exchange markets have largely ignored the resulting widening of short term rate differentials between Europe and the US. But with the trend likely to persist in the near term, widening differentials could begin to weigh at the margin on European currencies versus the US dollar. Any effect will be small, however. With monetary easing acting as an important shock absorber for the European economy, Europe’s relatively positive growth outlook will keep regional currencies solidly supported against the US dollar through the rest of 2025.

If Trump doubles down on his tariff war when the 90-day suspension ends in early July, monetary easing will help to insulate Europe from the sort of shock-induced recession that will threaten the US. And if Trump backs off tariffs, looser monetary policy will allow Europe’s increasingly convincing domestic credit upturn to bed down. Either way, easier monetary policy will help to accelerate a much-needed rebalancing of the continent’s growth model away from external demand and more towards domestic demand.